A Greenlandic Tale

During the summer of 2023 I was invited to be a benthic taxonomist on board the research vessel, Tarajoq, while it undertook fishery surveys of Atlantic Cod and Shrimp for the Greenland Institute of Natural Resources. The opportunity arose through a colleague from the University of Plymouth and was perfectly timed alongside my duties as a post-doctoral researcher at the University of Nantes. In this post I would have many learning experiences, increase my knowledge of fisheries, provide assistance to the annual monitor efforts of Greenland and develop international collaborative connections.

10th July

Today marks the first day of what I expect will be a spectacular trip. My friend Simon dropped me at the airport with good time. Yet, all the normal anxieties and doubts of going through airport security gripped me, but, as always, there were no issues. We took off from Nantes in glorious sunshine with a gleam of perspiration coating my forehead. This being partly due to my anxiety at flying and partly due to dressing for the Copenhagen climes. It was an easy short flight with quite special views across the Wadden Sea dotted with islets, banks and channels. The clear views and smooth flight quite rapidly turned into a juddering uneasy descent into the city. The approach into Copenhagen, similar to that of Dublin, Hong Kong or Vancouver, seems to be straight into the sea with the runway appearing at the very last second. Once through the airport at the other end the walk to the hotel, which I have been booked into, could not have been easier. Having freshened up and deposited my luggage I quickly turned around and was on the metro into town. I have little to no knowledge of the city but had been given one recommendation. Therefore, I headed straight for “The Little Mermaid” known locally as “Den Lille Havfrue”.

It is a bronze sculpture of a young lady sat in a side-saddle style on a rock on the coast. The ripples of the boats’ wakes brush her feet while the tourists pose, and the pigeons pray on the treats of the unsuspecting crowd. Being a working port, Copenhagen has the industrial concrete factories overlooking the water, while also containing a plethora of quaint small wood or red brick façade houses. This quick sojourn in the Danish capital was an added bonus. The real journey starts tomorrow.

12th July

The approach to Narsarsuaq was the most breathtaking view I have ever seen. Flying in we descended through the low clouds that stretched over the vast north of Greenland. As far as the eye could see were pure white glaciers that gave sharp contrast to the dark crags of rock, towering above even us on our descent. The landing approach brought us gliding in over the fjord where my new home, Tarajoq, sat waiting.

I had never seen glaciers or icebergs up close before but already within less than 24 hours I had become desensitised. Being formed by glacial movement, I see strong similarities between the Greenland landscape and the glens of the Scottish Highlands. We were alongside (in the harbour) at Narsaq waiting for the last members of the crew to join us. During this time I had the not-so-minor task of familiarising myself with Greenland Fauna.

Approaching Tarajoq through icebergs

16th July

Life on board Tarajoq was now starting to fall into a routine, the most breath-taking, stunning and surreal routine but not without numbing fatigue at the end of each shift. The cruise personnel were split into cooks (most important), ‘fish people’ (fisheries scientists), benthos people (us), deck crew, mechanics, helmsmen, skipper and cruise leader. We sailed up the east coast of Greenland, going from predetermined station to predetermined station. At each, we carried out a fishery trawl. All personnel were split onto shifts, so, as a whole, we fished 24 hours a day. My shift was midday to midnight and alongside the fish people we sorted through each catch.

The fish people took the fish and we took everything else. After a few days the wee beasties we caught were mostly becoming known to me, meaning our job of sorting, identifying and counting was becoming easier. While a lot of what we caught was similar between trawls we were starting to get mind-blowingly cool species and specimens too.

So far, we had caught and released with a tag, 3 Greenland sharks. At over 4 metres long they will all have been very old. When I say old, I cannot be sure, no one is, but it is likely they are older than the USA, maybe even alive during the Tudor times in the UK. Other amazing specimens of fish had also turned up, including multiple 30 + kg Cod, Halibut, Pollack and Rays.

Once my shift was done, especially after processing 700kg of sponge by hand, I was in need of a cold dip. While swimming in the sea was out of the question, we did have a huge dunk tank and a tap that drew sea water at around 4°C from the water around us. This allowed cold dips before turning in for the night.

We were skirting around but also through vast ice flows that were both spectacular to see in the day and terrifying to hear in the night, as we smashed our path through them.

The Bow of Tarajoq Gliding through the Water.

22nd July

The routine continued: wake up; take a multivitamin; grab a coffee and head to the bridge; admire either the beautiful vistas or rolling waves, whale blows, icebergs and Greenlandic mountains or feel the chill of fear looking out into impenetrable fog with icebergs looming out of the nothingness; then it would be time to eat before descending to the factory to sort, identify and count all species we caught within the trawl.

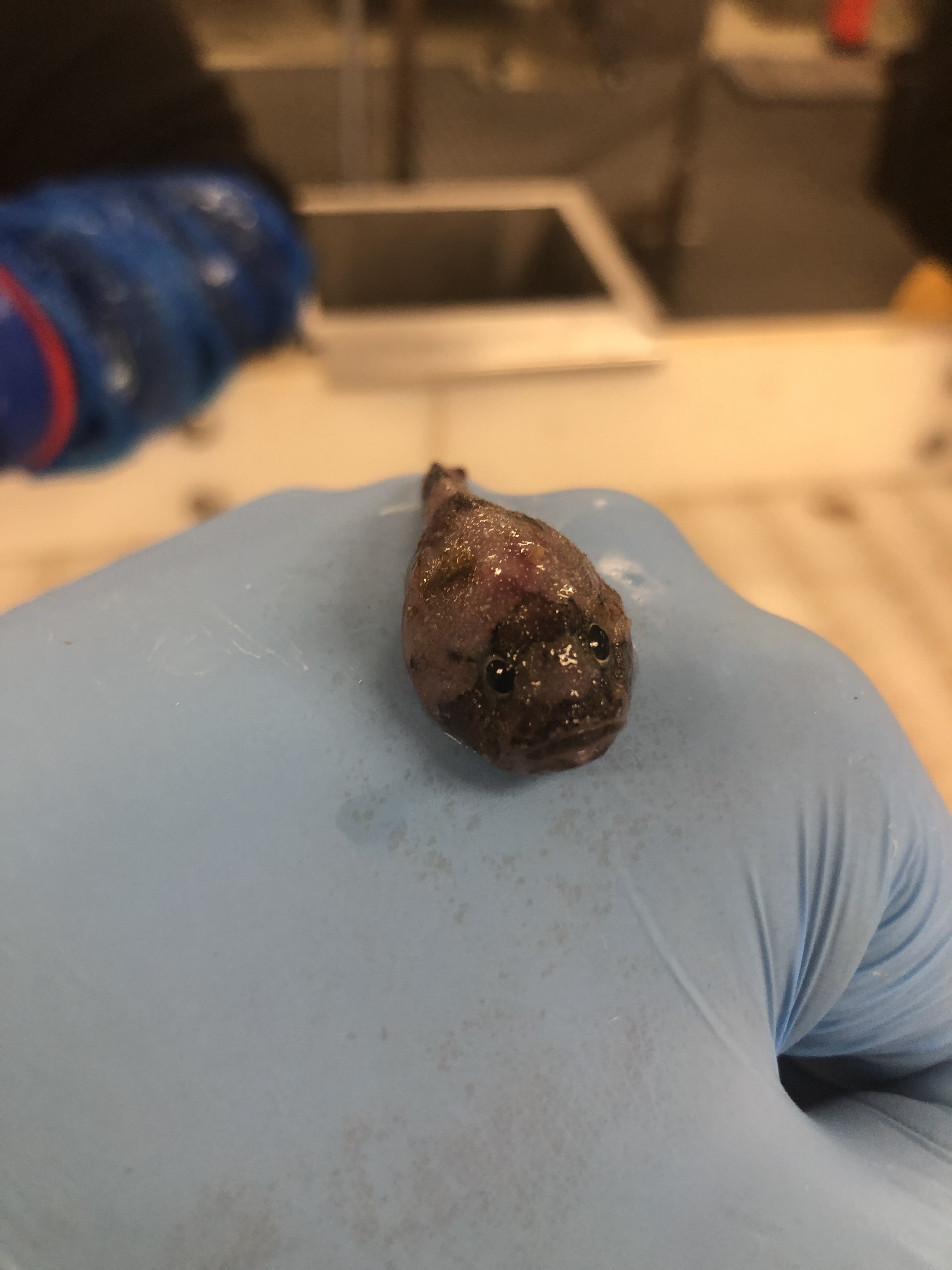

As we headed north along the eastern shelf of Greenland we could feel the cold intensifying. This was most apparent during my evening “swims”. The “swimming pool” was a reconstituted fishing box, previously used to store fish on ice to keep fresh; now it was filled daily with sea water of around 1-6 °C and sat in by myself and others of the crew. While the shock to the system seems extreme, the serenity I felt being sat in near-freezing water after a 12 hour shift spent lifting and moving (often entirely by hand) up to 4,500 kg of sponge was so relaxing, revitalising and reinvigorating. This cold dip then helped, while Tarajoq rocked with the swell, to send me off to the most tranquil, unbroken sleep I have ever experienced. The trawls, apart from literal tonnes of sponges, have yielded an amazing range of species from ancient Greenland sharks, monster cod and halibut to intricate deep sea Paragorgia corals. So far, the highlights had been the cute and sassy bobtail squids (Rossia sp.), grumpy octopuses (Bathypolypus sp.) and a small star covered smoothhound (Squalus acanthius). The trawls had even yielded long dead specimens: the vertebrae and a rib from some sort of whale.

In between trawls we got up to an hour of break, if the previous trawl didn’t catch too much. In that time, I took to sitting on top of the spare trawl nets, which were stored on the upper decks, looking out to sea, just waiting for the blow of a whale or the passing flight of the many sea birds that share these fishing grounds. We were gliding across almost gloss smooth waters but this was just “the calm before the storm”.

The cook told me we were about to meet a summer storm. If this happened the skipper’s job would be to decide where to weather the storm. As we wouldn’t be able to fish during the storm we would need to hide either inshore in one of the many fjords along Greenland’s east coast or head further offshore in deeper, calmer waters. Both scenarios would have had their advantages and disadvantages but only once the storm arrived could the decision be made.

27th July

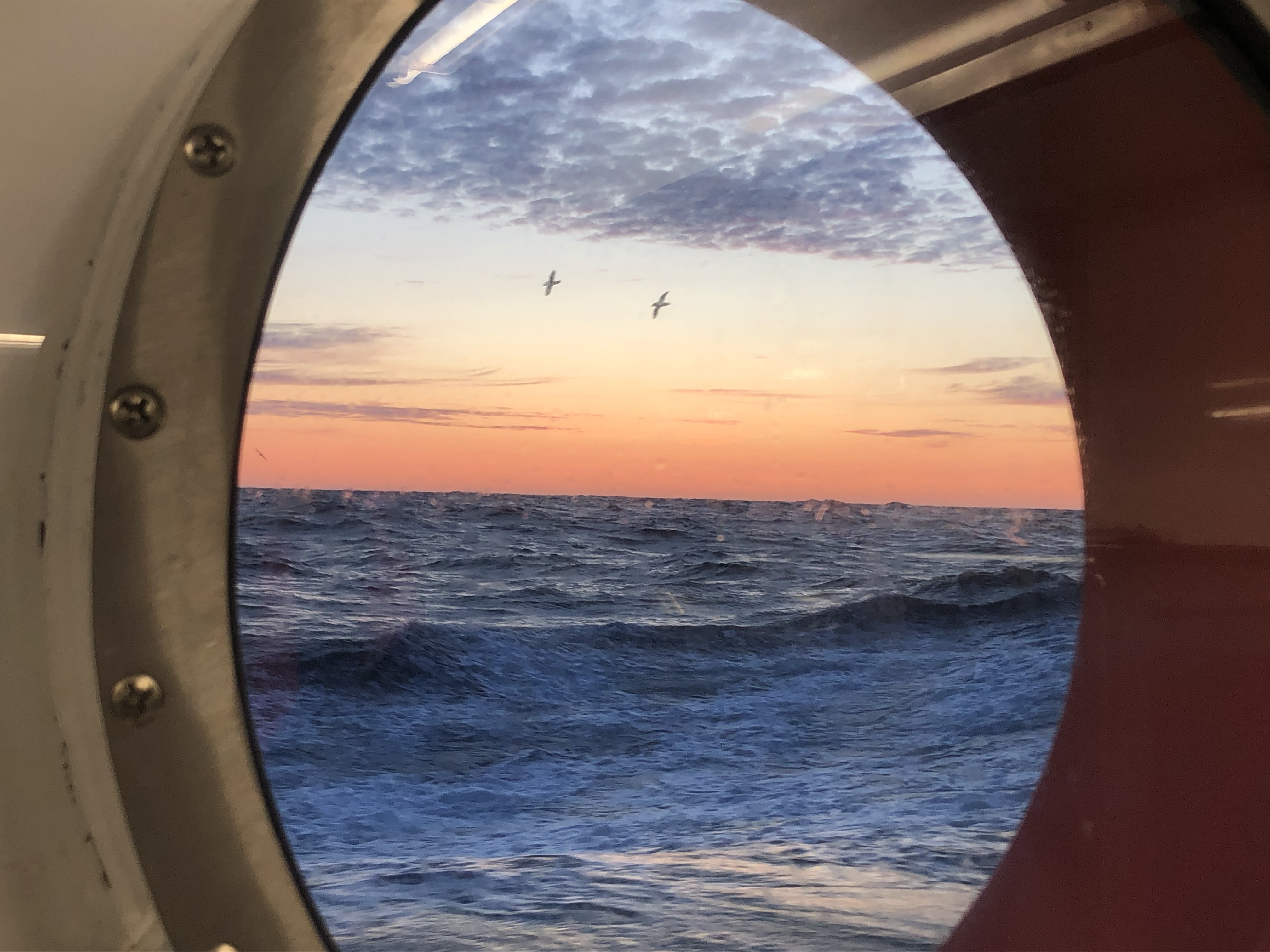

Thankfully the weather forecasts were correct, and a quick steam up north meant we skirted the storm, avoiding the worst of the weather. That being said, we still were exposed to the odd 5-10 metre wave with consistent 4 metre rolling swells for 3 days. The rocking motion made my sleep even better, although I know many who barely slept a wink. All crew and researchers got into the habit of continuously swaying, pre-emptively moving with the ocean rather than against it. As the storm abated and the weather cleared it allowed for one of the most vividly coloured sunsets I have ever seen. The whole world turned to sepia in the orange-red glow, giving the appearance of a dramatic fire raging just out of view. With it the sunset brought thin streaks of purple cloud, forming wisps of colour across the expanse of clear blue sky. After days that felt like weeks of close fog and clouds, the clear skies all the way to the horizon gave a feeling of relief. The sea was beginning to calm, although it still held some of the energy of the storm.

This calming gave way to the now regular spouts of air and water signifying the continual migration, movement and searching for food by the biggest animals to ever live. While a professional or even an avid amateur can tell the whale from the shape, size and frequency of its breaths, I could not The only species easy to identify, which whalers took great advantage of, is the sperm whale. The elongated head and offset nostril means a sperm whales spout shoots out at 45 degrees forward and off to one side. I had now seen many spouts of air, many off to one side, yet apart from the momentary glimpse of a tail or back, I hadn’t seen any of these whales up close.

A Whales Spout alongside Sunset.

My day-to-day shift continued as before with the odd species alluding me, but most were becoming well known to me. Alongside our fishing trawls we were also deploying benthic grabs, which take a grab of all species in the sediment, and video camera sleds, which in the same way as the trawl, is dragged along the seabed and captures all in its path. However, it captures organisms in their natural habitat and more importantly captures them only on film. Comparing the video, grab and trawl results side-by-side allowed us to see both the differences and similarities between the methods. As we came to the end of the survey each trawl became more special as I savoured each new identification. Once the survey was finished our next adventure would be the crossing to Iceland. The fine and clear forecast boded well for an easy crossing and while I was keen to see Iceland it would mean an end to this trip, which I was far less keen on.

29th July

Today marked the day when all sampling sites had been sampled. As with most fieldwork this trip included a few days of contingency for bad weather or equipment failure. However, through luck, efficient planning and hard work we had finished early. We still had other duties, such as cleaning, equipment maintenance, as well as trying to tag as many Cod (Gadus morhua) as possible. During this increased downtime we were sailing along the Greenlandic coast, over calm seas, under clear skies and alongside a vast array of glacial mountainsides. This route brought us closer to more icebergs, which drifted along beside us, often following our wake, driven by the currents on the surface and at other times moving at odds to local wind, waves and currents.

Being closer in to the shore brought us nearer to the playgrounds of a range of species. Unlike when we were offshore, surrounded by Fullmars and the occasional spout of migrating whales, inshore we saw a variety of seabirds and larger pods of whales. Gannets, which I had not spotted so far, now circled us, occasionally pausing and then plummeting into the cold waves, and Petrels flitted mere centimetres above the lightly moving water, giving the illusion of dancing across the peaks and troughs of the barely shifting swell. With the days of contingency not wanting to be wasted, the ships primary goal was to find cod. Up until that point we had been trawling specific stations to assess, in a standardised way, the distribution of this highly prized fish. Now we were on the hunt. If we could catch a large quantity we could insert tags into the fish that means when that individual is caught we can see where it ends up. Each tag was a small plastic streamer with a unique ID number. This means any fisher who catches a tagged fish can tell the Greenlandic fisheries institute where and when it was caught. These types of passive tracking can allow researchers to find out where fish go and when they go there, to better understand and therefore manage these fish.

31st July

After two and a half days, still working on 12 hour shifts, we had managed to tag over 2,000 cod. The work was short and intense; when a trawl came up, if it has cod we tagged them. If no cod came up then the trawl was emptied, reset and redeployed. When the trawl was full of cod we jumped to action stations. Firstly, all cod in the trawl were separated from the rest of the catch and placed in a holding tank. These were then left and monitored for health and survival for half an hour. Alive individuals were selected from the tank, laid out on a measuring tape to be recorded, a small plastic tag inserted into the cod alongside the dorsal fin and straight away released back into the sea.

This method was the same for all species we tagged throughout the trip, with the exception of the Greenland sharks, which were measured, tagged and released on deck as quickly as possible, to minimise time out of water and therefore stress to the animal.

However, the last trawl for this trip had come up; the last cod tagged; the last organism identified.

Sometime that day we would set sail for Iceland, crossing the Denmark strait and bound for Reykjavik. The crossing would take around 24 hours and we cleaned and tidied to keep busy. As the shift structure ended for all scientists, we played a game of ‘who can stay up latest’ for the night shifters and ‘who can wake up earliest’ for the day shifters. Over the last few days, we had slowly been transitioning to Icelandic time from Greenlandic time. With the last trawl came two huge and beautiful Greenland sharks.

Over the last 21 days at sea we had caught 7 of these slow, hardy giants, yet, I was still in awe of them every time. Their size and age just made me wonder what had happened over their lifetimes: what ships had sailed above them? Unbeknownst to them, did they cross the path of the Titanic or witness the U-boats of World War 2? With a potential age of more than 500 years, did they even see the Niña, Pinta and Santa Maria as they sailed to discover the people already living in North America? Very unlikely given the route Columbus took but the incredible age of these creatures and their relatively unknown behaviour highlights how little we still know about our oceans.

3rd August

It was my last night in the North. We landed in Iceland in Hafnarfjörður the day before and, after being cleared by customs, were allowed to get our feet on dry land. After almost 3 weeks on board, being ashore was a big shock. It was interesting to realise how continuously noisy the boat had been: the constant thrum of the engines, the crashing of waves, the booming sound of our hull hitting icebergs. All these noises just faded into the background. This made the still, calm, quiet of land feel almost eerie, perhaps too quiet! Hafnarfjörður is only 6 km south of Reykjavik, so we quickly made the short trip to the capital. After visiting the magnificent cathedral, which my sister tells me was informed by the ‘post-industrial rationalist movement in Holland and Southern Germany’, we decided to wander around Reykjavik but somehow got continually waylaid by liquid refreshment. The dry ship rules of the three weeks had produced a healthy thirst. From some extensive tasting I could conclude that the brewing culture in Reykjavik is amazing, the only drawback being the eye-watering price tag for a pint: £8-£10!!

This was my last night as a scientist on board the research vessel Tarajoq. My travel home would see me fly from Reykjavik to Paris then catch a train from Paris back home to Nantes. I would be lying if I said I wasn’t keen to be heading home but it would also be a huge lie to say I hadn’t loved this trip. It kept me on my toes with hundreds of new experiences. I had been so active carrying baskets of sponges to identify; washing down the grab we had used to sample mud from over five hundred metres depth; helping tag cod or counting and recording hundreds of jellyfish at a time. When not physically active the intellectual tasks had been just as rewarding, working out the taxonomic identities of different deep-sea spiders, squid, starfish or any number of other groups of species. The work itself had been extremely fun, with brand new species almost every trawl.

However, as fun and interesting as all these elements had been, the overwhelming comfort I felt at being on a boat, at sea, travelling across the great expanse of the ocean outstrips them all. It makes me realise that wherever I am, whatever I do, it must include being on, in or under the sea.